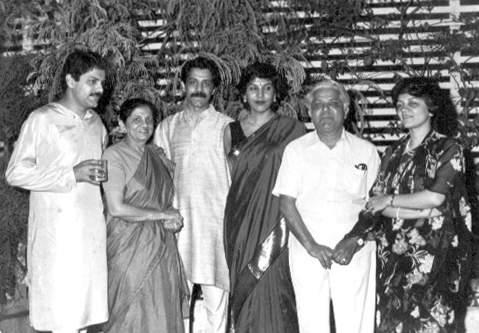

The Kapur Family

Memory Contributor: Neera KapurPicture caption: The Kapur Family, Bombay, 1990This photograph is probably the only image where the family....

Read More

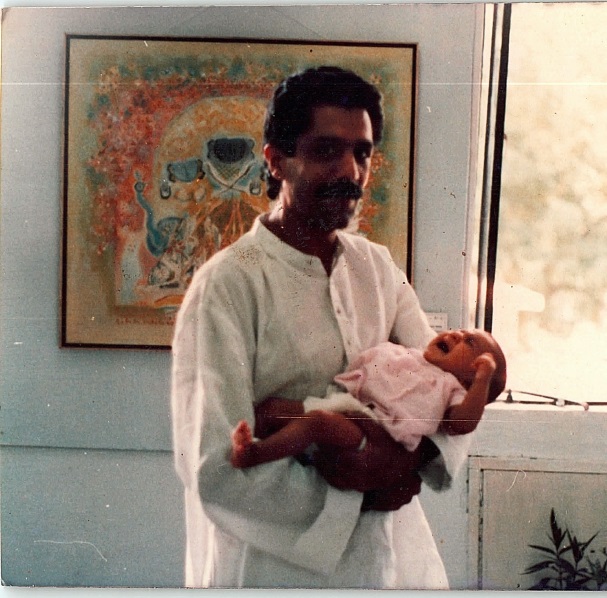

Memory Contributor: C.Y Gopinath, Journalist

The first time I saw him, I was mildly annoyed. It was 12 years ago and the time was close to midnight. Our sleep was disturbed by Rippan standing in the driveway two floors below and calling out to my sister. She dropped whatever she was doing, picked up her art materials, and vanished for hours while the parents conjectured about what was going on. I wondered why Rippan never bothered to come up to say hello.

We didn’t know, any of us, that this slight young man carried in his belly a fire much more fierce than ordinary people possessed. My sister in art school then was merely one of the dozens who had been infected by Rippan’s cause. According to him, he was only one human being, and there was far too little time. Everywhere children were being brutalized, scarred, and battered. They were being claimed by destitution, discrimination, disease - every inequity that cold, unfeeling minds can conceive and construct. To Rippan, no life had meaning if it could not respond to the violence that we subject our children to. Lesser individuals might have had time to say hello; Rippan was always behind schedule. I did not understand the zeal for a long time; it took even longer to acknowledge that it was sacred. I have a hazy recollection of a long, heated debate with Rippan in his house. Why? I asked him one evening, did he carry such a low opinion of people who left CRY? I had heard that Rippan almost took it as a personal insult when someone moved away from working for children. Is it not enough, I asked him, that people do what they can, to the extent they can, for as long as they can? Rippan was always impatient with such intellectualism. He politely parried with me for a while and then wound it all up with, “Look, I don’t have time to argue about these things. It’s not enough that you do what you can do. You have to do more than you can do. Otherwise, it’s not good enough!"

He lived fervently by his own rule; by 40 he had packed several eras into a lifetime of dreaming and doing. During his last days in the hospital, right till the time came to leave, he was planning new conquests, spinning detailed tales of aftermaths and consequences, sure that no one, not even God, would have the heart to interrupt such a vital enterprise. I don’t think, though, that Rippan believed in God. The fact that children needed CRY must have somehow been proof to him that if there was a divinity, it didn’t care very much. Rippan cared, and cared more than he ever revealed. He was not given to mush or melancholy, and a love that did not express itself in a deed was no love in his view. But today, in his wake, it is clear that Rippan, of all the humans I know, loved uniquely all his life, in ways that we cannot and dare not.