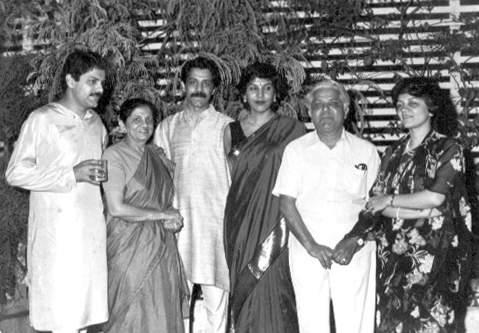

The Kapur Family

Memory Contributor: Neera KapurPicture caption: The Kapur Family, Bombay, 1990This photograph is probably the only image where the family....

Read More

Memory Contributor: Tara Sabavala

Picture Caption: Tara Sabavala with JRD Tata at the Jehangir Art Gallery, Art for CRY, Bombay (now Mumbai), 1988

After college in St. Xavier’s, I decided to get into the advertising business. I had two options, O&M (now Ogilvy) who were looking to recruit but wanted a two-year bond which I wasn’t ready for, or Lintas Advertising (now Mullen Lowe) that offered an unpaid 6-month apprenticeship. I took up the latter and stayed in the business for 10 years after.

Alyque Padamsee, the CEO of Lintas at the time, had a strong social and charitable side to his personality – and even offered pro bono services to several NGOs. Lintas also had a monthly session called the ‘Prayer Meeting’, inherited from Hindustan Levers (now Hindustan Unilever). The sessions weren’t about religion but the experiences of people from all walks of life. I remember one of the speakers was a gentleman called B.C Dutt. He had worked in Lintas, in the administration department before taking early retirement to work in a village in Raigarh. When he spoke about his experiences, it got me thinking whether I wanted to spend the rest of my life selling Rin, or deciding where the logo should go on an advertisement.

It took me a year to process that change within me and I began looking at options. I knew Neera Kapur (Rippan’s sister) who was on the CRY board at the time and Gitanjali Khanna as friends. Maybe it was talking with them that veered me to CRY. It seemed interesting enough for me to consider joining in. It was an organization with a middle ground, it wasn’t all grassroots and was geared towards development. I met with Rippan who came to my house with a presentation on video because I remember watching it on TV. I discussed a more detailed profile of my role with CRY. He told me very clearly that while the pay cannot match Lintas, everyone does get paid a bit and my salary was Rs 1500. I joined CRY in November of 1987.

CRY was small with only a handful of us and we got involved in virtually everything. I was also involved in fundraising, literally going door to door and selling advertising pages of the telephone directory to corporates. At that time, the idea of ART for CRY was being formulated and we all got pulled in to make it real. We were already in discussions with a sponsor for a substantial amount and had discussed 4 locations for the event, Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta, and Bangalore. But just moving the artworks around was a huge cost and the sponsorship fell through. I suggested looking to an old family connection – the Tatas. As a child, I grew up knowing JRD Tata. We decided to make a pitch to JRD whom I knew loved children. I remember Rippan was so nervous on the day of the meeting, he went home to change into a fresh white kurta.

At the slated time of meeting at Bombay House, JRD was there with the then director of Sir Dorabji Tata Trust, Mr. Rusilala. After hearing Rippan’s idea on ART for CRY, JRD began by asking several questions about the organization. He was impressed, serious as well as light-hearted – asking Mr. Rusilala, “Why do you think we should give money to these young people?” At the end of the meeting, JRD was convinced that what Rippan was doing was genuine. JRD then wrote personal letters to all TATA companies asking them to give money for ART for CRY.

Rippan had been dreaming about it for so long that when it came to life, he was overwhelmed. The day Rajiv Gandhi came, I remember I wasn’t there because I had taken a much-needed break to Lonavala for a weekend to recover from all the organizing. But in the end, the visibility CRY got because of ART for CRY put the organization on the map. It was a new effort to raise Indian money for Indian causes and it engaged individuals as well as corporates. CRY opened up a new interest in professional giving.

Having said that, the attitude of many donors is still that they don’t see our work as a worthy profession. They think it is what affluent people do in their spare time or is a job for people who don’t find a job elsewhere. People did give but they couldn’t see why we had to pay salaries to ourselves. But we were not a bunch of mere do-gooders. We also needed to be paid and live a life and contribute professionally. CRY made me see this, I began to realize that it was a profession like any else, and one needed to develop as many skills, knowledge, and strategies to work in this sector. I thought my advertising experience was redundant until I realized it wasn’t. However, for all the people who were hard to convince, there was an equal number who asked no questions.

Within the organization, growth was rapid and we were not structured very well. But Rippan was very open to new ideas and I even requested a Performance Appraisal system because I believed that while one’s heart is in the right place, we must be measured according to performance. Rippan encouraged us to do whatever we could with the experience we had. Rippan, Neera, Srilatha Batliwala, Geetanjali, and I use to sit in on all the board meetings. I remember meeting inspiring people working in the field – Gloria D’Souza of Parisar Asha, Sheela Patel of SPARC. I remember going to the MV Foundation as a Program officer and meeting Shantha Sinha. The work they were doing was pathbreaking. I was learning everything and as much I could, even if new, and it held me in good stead. Rippan believed in not dictating terms about what must be done with the money that was raised, he was listening to peoples’ and projects’ needs and molding himself to the sectors. That was a very important aspect to embrace when working in the development sector. Soon we got more program support and divided our work regionally. I volunteered to work on the program side because by then, I realized the amazing possibilities we could achieve connecting with the communities. It had very high rewards. Working for the cause broke a lot of myths about underprivileged children. Many people believe that the poor don’t want to be educated and that is a complete lie. I know that any parent for any economic class will do everything to ensure that their children get a good education. You don’t need to convince communities that education is important.

I left CRY in 1989 to establish Lintas’s new cell on Public Service Communication and in 1992, I joined Concern India. Now I work with the TATAs. But CRY brought about a great change in my life and I knew I wanted to spend my life working in development sectors. I have not looked back since; with so much learned and understood from scratch, I have done very well in all my engagements.