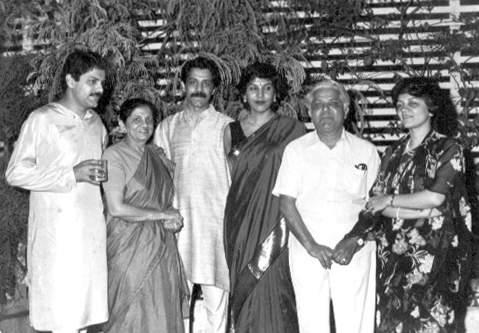

The Kapur Family

Memory Contributor: Neera KapurPicture caption: The Kapur Family, Bombay, 1990This photograph is probably the only image where the family....

Read More

Memory Contributors: Srilatha Batliwala, Pervin Varma

Srilatha Batliwala: I want to start by telling you about this image, not because I was present but because it reminds me of the Rippan I knew and brings back the nostalgic memories of the good work CRY and I have done together. In 1974, after I completed my Masters in Social Work from the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS), for eight years, I worked with Mr. Noshir Antiya, the Founder of FRCH (Foundation for Research and Community Health). He recruited fresh graduates as primary health workers to help operationalize and train women at the grassroots level, much like the Barefoot Doctor Model. He was a visionary who would straddle community health work, research, and policy advocacy. I was hired to do the bridging between all the areas. I trained many people and also set up an information system to keep a check on the policies. FRCH at the time focused only on women as ‘primary health workers’. But that work made me more curious about why women and female children bore the bigger burdens of life?

In 1982, I co-founded an NGO called SPARC in which we worked with the women pavement dwellers and looked at all the dimensions of gender power and discrimination. We began the work by reaching out to the poorest women in the city and empowered them to claim their citizenship rights.

I don’t remember how I encountered Rippan. I think we met at an event and he persuaded me to work with CRY, even if it was as an informal advisor. He wanted me to help systematize CRY’s grant-making and proposals. At the time, I had a lot of the arrogance of a ‘politically-committed grassroots activist’ and was dismissive of Rippan and his ideas. I was judgemental about what people like Rippan were trying to do. I thought of their ideas to be elitist, with all their fancy-schmancy marketing and felt that they didn’t understand social powers and discrimination. According to me, it was a ‘welfarist’ approach to get sponsorships of ten rupees from everyone, even though Sheela Patel who was the co-founder of SPARC, and a close friend even today, had worked with a sponsorship program at Nagpara.

With that baggage, if Rippan was able to get me to go to CRY, you can imagine what it says about his charisma. He had a mule-ish unwillingness to be dismissed. But he was no fool, he must have felt my attitude. Nonetheless, he wasn’t interested in my attitude but what I had to offer. I knew I needed to earn more, but Rippan continued to be persistent about wanting me there, so I finally joined, in part-time, and became a part of CRY, just post its infancy in 1986.

When I walked into Aakash Ganga, I was horrified – everyone was all squeezed up in that tiny room. But soon, I noticed the good side of CRY. Rippan used a rather intuitive way of looking at projects and deciding where to put the money. It was very subjective but if one applied objective criteria, it could be very questionable. (I had worked with Ford Foundation so I knew). For a while, even the biggest of philanthropists in the world had worked like Rippan did.

I had a rather interesting transformation while trying to understand CRY and Rippan’s vision. It began to satisfy my judgments of a radical activist. I began to see that there was indeed a vision and he had an intuitive understanding of power differences and social hierarchies. I appreciated the fact that he was trying to create a space for decent human beings. A lot of people who were contributing to CRY were donors from the working class like secretaries and peons. CRY was inspiring ordinary citizens to become a part of a larger social equity project and to think about issues that they normally wouldn’t. Rippan was pushing them to recognize the need to do something. I could have been dismissive about it but I realized that without these efforts, so many people wouldn’t be a part of it at all. Fortunately, my politics was influenced by my father and he encouraged me to think of ideas that were more nuanced. ‘Instinct’ may seem like an irrational response but it has a role to play when we think about grant-making. I didn’t recognize it at that moment but as my love and respect for Rippan grew, I became more aware of how his instincts come to play in his decision-making process. The bigger picture of CRY was becoming more clear to me – for instance, attracting big donor agencies. We had to create a more indigenous place of philanthropy and mobilize resources from Indians who wanted to give. When I wrote the first CRY strategy paper with the criteria for grant proposals (with some criticism about how everything had been managed so far), I also mentioned in it that at the end of the day, even if all the criteria were met, if one doesn’t have a good feeling about it, then one must trust those instincts.

Rippan was very upset when he read the paper and saw it as a searing critique, but he also sensed that this was the way the organization will have to work. I remember our chat – “You make it sound as if we have crores to give!” “You may soon have crores, so be ready. Then you will be visible and not a small shop. Right now people give out of goodwill and it will change. Then you will be under great scrutiny and someone or the other will raise complaints. No one ever thought you could take up UNICEF with greeting cards but you are no longer a kitchen table operation!”

CRY was already going to the field to consider many kinds of proposals. But now we wanted to support those whose approach to their work was more transformative. Many ideas were good but the proposals weren’t. I was used to getting snazzy proposals at Ford and it was a culture shock. I began to offer an orientation to grant writing and criteria: The questions one should ask and to engage in a dialogue with everyone involved. I remember once a guy told me, “This is like detective work!” and yes, in a way it was. I also asked Rippan to give me a list of people with whom I could discuss and get some perspective about the direction CRY would like to go in and interviewed all the trustees.

I also tried to discourage Rippan from trying to visit every proposal-project. Though once a project was deemed fit to consider, he would spend some time with them. He was so driven that he would come back from a flight at 3:00 am, and at 7:30 am he would set out for some field work.

For Rippan, the growth of CRY was a joyful as well as a painful journey. It meant he had to eventually surrender control and that was quite hard. CRY was his baby, his passion, and to let go of it meant that he will not be the final decision-maker, but then it would have more structure through which decisions got made. In retrospect, I think his worry was also the possibility that all fund distribution to projects might be devoid of any intuition, or emotional reasons. I remember his words, “This is all well, but we mustn’t lose our soul!” I may have been more impatient with that. I had to push him to think critically about what CRY was doing. To systematize CRY’s approach of not only what it will support but to also make it more robust to public scrutiny. NGOs were coming under scrutiny because of several reasons, one of them was The Naxal movement’s radical ideas. Also, Indira Gandhi was coming down on many NGOs. I was focussed on how to make CRY more robust with inquiry and that it must have an ethical stand and strength to stand by its beliefs. CRY was ready to make that change and we introduced a formal system of evaluating programs. As the new systems began to roll out (in phases), Rippan felt more secure.

I was at CRY for six months, after which, I went back to SPARC but I continued to work as a reviewer of CRY grantees. A few years later, sitting in the office of Ford Foundation in New York, I found myself looking at beautifully written and argued proposals again. Proposals that were in a strong position to be granted funds, but I couldn’t do it. I then wrote to Rippan that I learned something from him. If I couldn’t feel passion, deep commitment, and real feelings about social justice, it bothered me. It may be a nice project and its accounts may be clean but I just knew that it won’t make a deeper change. I had begun to see projects through Rippan’s eyes. Both our gut and actions must go in strengthening the good and making a better world, and maybe then we may find a world filled with hope.

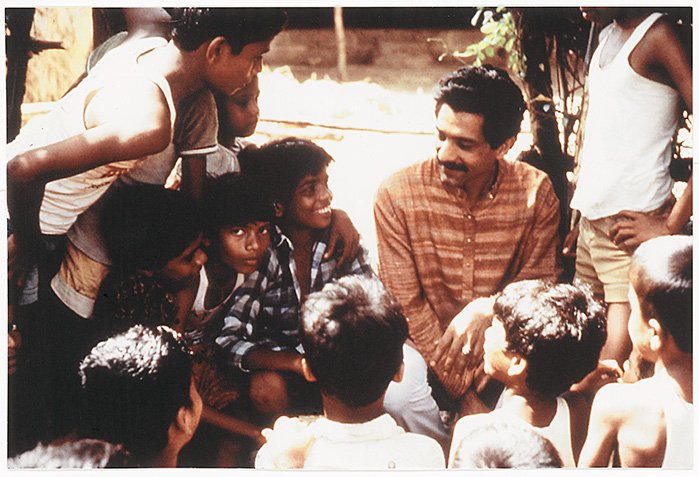

Pervin Varma: This picture of Rippan with the kids, laughing and chatting, reminds me of the event ‘Bal Sawaal’. I remember we were doing an event across three parks in Bombay. It was an awareness event and the children had painted buses; there was much excitement in the air. At one of the parks, Shivaji Park, there was a street theatre performance by the street kids there (a YUVA project). Meanwhile, a well-known local band who were to perform later that evening decided to run a sound-check. The kids requested them to stop the sound-check for only 8 more minutes but they simply wouldn’t. Flummoxed by their attitude, we asked Ratan Batliboi to speak with the band leader who turned around and said “Well no sound-check, no show, Boss!” and carried on.

The kids couldn’t perform and they were devastated. The whole group performing got very upset with us and we asked them what we could do to make it okay. They insisted that they wanted to talk to Rippan. When I told Rippan what had happened, I was very nervous. Rippan simply replied – “You should have told them no show!”, and he immediately left for Shivaji Park.

The moment he arrived, he was surrounded by the kids who couldn’t perform and they started yelling and complaining. He listened to them calmly and said – “I am ashamed this has happened to you. If I was there, this would have never happened”. He explained to them what the event was about and invited the kids to perform on the stage; that very evening. Rippan kept his word and the kids went up on stage and performed.

This is what CRY is about. We do what is right for the children. They always come first.